On a normal Sunday morning, it began when Jennifer looked at me with a spark in her eye and said, "How about a train ride to Scarborough?" Something inside me lit up, and as the two of us told Tyler the plan, he began dancing and immediately donned his red bath robe, announcing, "I will be the boy and the train to Scarborough will be the polar express!"

Two hours later, we had ridden bikes into the city center in a downpour. Soaked and excited, we quickly locked up the bikes outside the train station, offered a granola bar and a Braeburn apple to a man who needed it named Cliff, and then ran towards Platform 5, Tyler's oversized bath robe billowing out behind him.

In Scarborough, the rain didn't let up. After a mile walk down Castle Road--with a brief interlude at Anne Bronte's gravestone at St. Mary's Church--the castle appeared, hunching down as a giant and lowering his hands for visitors to walk through. In the giftshop, we flashed our cards while Tyler tried out some swords, and then tried some crackers with chutney, which he promptly gagged out and onto his shirt and Jennifer's hands.

The next two hours held a slow crescendo of sunlight, until finally a massive rainbow broke the clouds and, as Jen remarked, dove into the ocean beyond the cliff of the castle. We ran and ran and ran--all the while shouting out whatever things came to our heads. We splashed through puddles and tried to wrap our heads around that fact that the castle has existed for a thousand some odd years.

"This is the greatest day I ever had!" Tyler shouted as we ran, and it was hard not to agree.

Leaving the castle, we walked down to the beach and constructed our own. Cold winter sand collected from our gloved hands and rose to form a respectable little tower. We draped seaweed that has washed ashore from all angles of our castle.

The sun slowly made his excuses and ducked out of our day, but not before the thirty-minute-old sand castle and the thousand-year-old stone castle aligned. Looking at them both together from the shore, their sizes were similar. While one would fade with the oncoming waves, in that moment both were just as strong.

In Rachel Joyce's remarkable novel The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, the protagonist slowly chooses to make what began as a brief walk to the post office into a cross-country journey. Harold continually faces the foes of any adventure that involve the feet and the heart--but again and again Harold makes that quintessential choice: to keep going. As he continues onward, he deals with the regrets of his life--and how his past failures as a man, husband, and father have haunted his present. What is most moving about Harold, though, is that his walk is a promise to face what his life has been, and an attempt to remake it over again.

Joyce writes of Harold, "It didn't matter that he had not planned his route, or bought a road map. He had a different map, and that was the one in his mind, made up of all the people and places he had passed." As Harold walks his journey, he slowly learns to become vulnerable--connecting with others in ways that are authentic and nonjudgmental, and learning to view his own past in this light too.

The thing about castles is that we are often so much more fascinated by those that others have built. We may stand at the boldness of their stone walls and gape at the sheer magnificence of them. And this is important.

But what is just as important is making our own maps, too. Pushing the cold sand into walls that slowly rise and reach up towards the horizons in our very own eyes. Just as important is the need to make maps from all the relationships within which we find ourselves--seeking significance not via accomplishments on the grand scale of years, decades, and centuries, but on the grand scale of the human heart--the way in which we empower it within others, and within ourselves.

In the end, waves come and collect all our work--whether within the tide pushing up against the shore to take the sandcastles we build in a day--or the time pushing up against our lives to bring us to a new home.

What lingers longer than ourselves is never the walls, never the castles themselves, but always the love in which we create and cast our visions onto existence. That is what both allows us to endure, and endures.

One Writer's Journey Through Parenting, Teaching, Writing, Faith, and Social Justice. A.E. Housman once claimed that "poetry is not the thing said, but a way of saying it." These are my attempts at a way of saying it. Too often, we erect walls where a few stoplights would do the trick. Consider these posts stoplights along the way.

Monday, December 31, 2012

Thursday, December 27, 2012

Mucking About

There's a beautiful line in The Shawshank Redemption where Red (played by Morgan Freeman) says: "Andy Dufresne--who crawled through a river of shit and came out clean on the other side." It's a poignant moment in the film when Andy (played by Tim Robbins) has escaped prison by tunneling his way through a six-foot thick concrete wall and then crawled through the jail's sewage tunnel to land himself in a river, and in freedom.

Though much less dramatic than Dufresne's journey, I had to laugh yesterday as Jennifer and I and Tyler walked through a large field near our house full of sheep, and thus--of course--also full of sheep excrement. Pools of water gathered like lonely bystanders across the field from the previous night's heavy rain, and tracks and paths had converted themselves to mud that sometimes ran deep enough to engulf even our boots.

With soaked socks and to the narration of squelch-squerch, squelch-squerch, squelch-squerch, we ran onwards past the sheep and over small wooden bridges and without any cap for our voices or our laughter. We yelled the things that came to our minds--and we sometimes yelled Freedom! just because it felt like, well, freedom.

Tyler continued to run ahead of Jennifer and I as he said, "I will be the leader!" and Jen and I took great joy in not having to shout ahead, Wait there for us! or Watch out for that car! or Watch out for that massive crowd of people!

We watched Tyler run through the sheep excrement, the mounds of dirt, and the grass that even with mud and flood refused--like especially stubborn cowlicks--to lay down quietly and hide.

And Jennifer and I ran too. We held hands through padded mittens and gloves and as we ran all I could think was this: No matter how crowded life gets in other ways, no matter how hard the hard hits, or how sharp the shocks of the future will surely announce themselves, there is now. There is this moment of running through a field abandoned by people but peopled by sheep. And I love this.

I used to work as a sherpa for a wonderful program called La Vida (now led by an amazingly gifted leader named Nate Hausman, and first created by another amazingly gifted leader named Rich Obenschain). The program brings groups of students--sometimes incoming Freshmen to Gordon College, where I attended, and sometimes groups of high school of even middle school students--into the wilderness of the Adirondack Mountains. For two weeks, groups travel the mountains, pumping their own water from the rivers, sleeping in the same clothes each night, taking no showers of baths, and hanging food in a bear bag each night--high aloft in the trees so as not to tempt the black bears. One of many beautiful slogans from La Vida is: Be You, Be Here, Be Now.

While there is proper--and important--place and time for planning and thinking ahead, there is also an essential need in us to run freely now. To think not of what has happened (and the guilt, shame, or regret it tries to tag us with) and to think not of what may happen (and the worry and fear we sometimes associate with the future) is sometimes so important to our hearts because they simply can't bear those burdens.

Sometimes our hearts need to move through the dirt, the excrement, the muck in order to find those places of freedom where we can be washed clean.

yesterday, mucking about in the sheep fields, I'm grateful for the freedom I saw on Tyler and Jen's faces. And I'm grateful for the freedom I felt stretch across my own.

Though much less dramatic than Dufresne's journey, I had to laugh yesterday as Jennifer and I and Tyler walked through a large field near our house full of sheep, and thus--of course--also full of sheep excrement. Pools of water gathered like lonely bystanders across the field from the previous night's heavy rain, and tracks and paths had converted themselves to mud that sometimes ran deep enough to engulf even our boots.

With soaked socks and to the narration of squelch-squerch, squelch-squerch, squelch-squerch, we ran onwards past the sheep and over small wooden bridges and without any cap for our voices or our laughter. We yelled the things that came to our minds--and we sometimes yelled Freedom! just because it felt like, well, freedom.

Tyler continued to run ahead of Jennifer and I as he said, "I will be the leader!" and Jen and I took great joy in not having to shout ahead, Wait there for us! or Watch out for that car! or Watch out for that massive crowd of people!

We watched Tyler run through the sheep excrement, the mounds of dirt, and the grass that even with mud and flood refused--like especially stubborn cowlicks--to lay down quietly and hide.

And Jennifer and I ran too. We held hands through padded mittens and gloves and as we ran all I could think was this: No matter how crowded life gets in other ways, no matter how hard the hard hits, or how sharp the shocks of the future will surely announce themselves, there is now. There is this moment of running through a field abandoned by people but peopled by sheep. And I love this.

I used to work as a sherpa for a wonderful program called La Vida (now led by an amazingly gifted leader named Nate Hausman, and first created by another amazingly gifted leader named Rich Obenschain). The program brings groups of students--sometimes incoming Freshmen to Gordon College, where I attended, and sometimes groups of high school of even middle school students--into the wilderness of the Adirondack Mountains. For two weeks, groups travel the mountains, pumping their own water from the rivers, sleeping in the same clothes each night, taking no showers of baths, and hanging food in a bear bag each night--high aloft in the trees so as not to tempt the black bears. One of many beautiful slogans from La Vida is: Be You, Be Here, Be Now.

While there is proper--and important--place and time for planning and thinking ahead, there is also an essential need in us to run freely now. To think not of what has happened (and the guilt, shame, or regret it tries to tag us with) and to think not of what may happen (and the worry and fear we sometimes associate with the future) is sometimes so important to our hearts because they simply can't bear those burdens.

Sometimes our hearts need to move through the dirt, the excrement, the muck in order to find those places of freedom where we can be washed clean.

yesterday, mucking about in the sheep fields, I'm grateful for the freedom I saw on Tyler and Jen's faces. And I'm grateful for the freedom I felt stretch across my own.

Monday, December 24, 2012

The Journey from A to B and the Chance for Greater Love

I think most of us seek to get from A to B in the most efficient, least dangerous, most pain-free, worry-free, pleasant, comfortable way. If it's at all possible for us to get from A to B while enjoying a drink with a small umbrella in it, or while having our feet massaged, or while having someone read aloud passages from Fyodor Dostoevky's The Brothers Karamazov while enjoying a drink with a little umbrella on it and having our feet massaged--then we'll go for it.

But the thing I am noticing again, and again, and again, and again is that around this particular day, when we think of Christ's birth, is that the whole nativity story makes absolutely no sense. Zero sense.

On a scale of sense-making, where zero is the idea of trying to squeeze an oversized lampshade down a red stirrer from Dunkin' Donuts, and ten is try to use a Dunkin' Donuts red stirrer to stir your coffee, the nativity story is a zero.

Forget zero, the nativity story nets a negative number.

But maybe that makes a whole lot of sense. God decides to send the savior of the world to earth, and if we were God, we'd be running the numbers. Immediately, we'd have cost-effectiveness graphs--bam!--and we'd be searching all the crime stats for the absolute safest possible town in the absolute safest possible country in the whole planet. And we'd be choosing the most experienced--and wealthiest--couple to find as his parents. And we'd be sure to load up our savior with heavy does of life insurance, health insurance, fire insurance, home insurance--the whole deal. And we'd hire the best consulting firm to process exactly how to raise that savior, and how to prepare the 'consumer' to meet and greet that savior. And--no doubt!--we'd have a few book deals lined up for the uncles, aunt, parents, and for the savior himself. From the get-go,., we're talking multiple deals, at auction.

But God didn't work that way. Instead, God choose the absolute most culturally dangerous situation--a young, unmarried virgin--to become pregnant. Then, God choose the exact moment before a census, so that Joseph and Mary would have to travel during her pregnancy. And we're not even talking here about a three-hour jaunt to the in-laws. We're talking about a multi-day journey wherein food is in short supply, nights are cold, an old donkey is exhausted. And then--to top it all off--God chose to lead Joseph and Mary to the barnhouse to birth the savior amidst hay (which is really quite pokey, prodding stuff, no matter what anyone says), animal poop, and absolutely no plan.

Bam. There they are: new parents away from home with no help and no money and no place to stay.

In essence, then, God brought Jesus into the world in the precise, most specific, utterly exact opposite way any of us in our sense-making minds would choose to do.

But, if we really think about it, it does kind of make sense in a weird way.

It makes sense, especially, if you think about life before children and life after children.

Sure, the journey to get anywhere before kids looks enticing. That nice, slender, thin line. And then before we know it: B! We made it to B! But the thing about the ridiculous journey to get from A to B after kids is this: by the time we get to B, we're different.

B is the same no matter how we travel, but we're different. All those crazy spikes and drops and whirls and twirls have changed us. And a lot of times, not for the better. I wish I could always journey from A to B and encounter those loops and swoops with great hope, faith, and even love. But I don't. However, I think the latter journey affords us the opportunity that we all are desperately seeking beyond the quick fixes and the cost-effectiveness strategies.

The second journey allows us the space to become what we could become.

Which leads us back to God. If he allowed Mary and Joseph to have that first kind of journey to welcome their son Jesus, I wonder what kind of parents they'd be. My hunch is maybe not as good. Something about the danger of the journey, the lack of safety and insurance and the crazy loops and swoops got them to point B as different people--stronger, more faithful, more loving.

Tonight, on the eve of Christ's birth, I keep thinking about this prayer Mother Teresa used to pray whenever something truly difficult occurred: Lord, help me see this moment as a chance for greater love.

And maybe that one part of what God was thinking when he gave Mary and Joseph that second kind of journey from A to B. The nativity story isn't easy, but maybe that's because God knew that to get them to point B in the fastest, most comfortable, easiest way possible wouldn't prepare them for the great love that was about to be unleashed in and through and for them.

And maybe the same is true for us. On whatever loop or swoop or curl or twirl or whirl we're on in our journey, maybe part of the reason we're on it is to prepare us to be the kind of people we need to be so that when we finally reach point B, we'll actually be ready. We may fall down, exhausted, when we get there, but our arms will be open and we'll be smiling and maybe we'll even look back and see everything we went through as those chances for greater love.

But the thing I am noticing again, and again, and again, and again is that around this particular day, when we think of Christ's birth, is that the whole nativity story makes absolutely no sense. Zero sense.

On a scale of sense-making, where zero is the idea of trying to squeeze an oversized lampshade down a red stirrer from Dunkin' Donuts, and ten is try to use a Dunkin' Donuts red stirrer to stir your coffee, the nativity story is a zero.

Forget zero, the nativity story nets a negative number.

But maybe that makes a whole lot of sense. God decides to send the savior of the world to earth, and if we were God, we'd be running the numbers. Immediately, we'd have cost-effectiveness graphs--bam!--and we'd be searching all the crime stats for the absolute safest possible town in the absolute safest possible country in the whole planet. And we'd be choosing the most experienced--and wealthiest--couple to find as his parents. And we'd be sure to load up our savior with heavy does of life insurance, health insurance, fire insurance, home insurance--the whole deal. And we'd hire the best consulting firm to process exactly how to raise that savior, and how to prepare the 'consumer' to meet and greet that savior. And--no doubt!--we'd have a few book deals lined up for the uncles, aunt, parents, and for the savior himself. From the get-go,., we're talking multiple deals, at auction.

But God didn't work that way. Instead, God choose the absolute most culturally dangerous situation--a young, unmarried virgin--to become pregnant. Then, God choose the exact moment before a census, so that Joseph and Mary would have to travel during her pregnancy. And we're not even talking here about a three-hour jaunt to the in-laws. We're talking about a multi-day journey wherein food is in short supply, nights are cold, an old donkey is exhausted. And then--to top it all off--God chose to lead Joseph and Mary to the barnhouse to birth the savior amidst hay (which is really quite pokey, prodding stuff, no matter what anyone says), animal poop, and absolutely no plan.

Bam. There they are: new parents away from home with no help and no money and no place to stay.

In essence, then, God brought Jesus into the world in the precise, most specific, utterly exact opposite way any of us in our sense-making minds would choose to do.

But, if we really think about it, it does kind of make sense in a weird way.

It makes sense, especially, if you think about life before children and life after children.

Sure, the journey to get anywhere before kids looks enticing. That nice, slender, thin line. And then before we know it: B! We made it to B! But the thing about the ridiculous journey to get from A to B after kids is this: by the time we get to B, we're different.

B is the same no matter how we travel, but we're different. All those crazy spikes and drops and whirls and twirls have changed us. And a lot of times, not for the better. I wish I could always journey from A to B and encounter those loops and swoops with great hope, faith, and even love. But I don't. However, I think the latter journey affords us the opportunity that we all are desperately seeking beyond the quick fixes and the cost-effectiveness strategies.

The second journey allows us the space to become what we could become.

Which leads us back to God. If he allowed Mary and Joseph to have that first kind of journey to welcome their son Jesus, I wonder what kind of parents they'd be. My hunch is maybe not as good. Something about the danger of the journey, the lack of safety and insurance and the crazy loops and swoops got them to point B as different people--stronger, more faithful, more loving.

Tonight, on the eve of Christ's birth, I keep thinking about this prayer Mother Teresa used to pray whenever something truly difficult occurred: Lord, help me see this moment as a chance for greater love.

And maybe that one part of what God was thinking when he gave Mary and Joseph that second kind of journey from A to B. The nativity story isn't easy, but maybe that's because God knew that to get them to point B in the fastest, most comfortable, easiest way possible wouldn't prepare them for the great love that was about to be unleashed in and through and for them.

And maybe the same is true for us. On whatever loop or swoop or curl or twirl or whirl we're on in our journey, maybe part of the reason we're on it is to prepare us to be the kind of people we need to be so that when we finally reach point B, we'll actually be ready. We may fall down, exhausted, when we get there, but our arms will be open and we'll be smiling and maybe we'll even look back and see everything we went through as those chances for greater love.

Friday, December 21, 2012

The Darkest Day of the Year

Today in England, the sun set at about 11:25 am. Okay, seriously: the sun set at 3:30 in the afternoon. (Though it sure felt like 11:25 in the morning.) But it rose at about nine o' clock, and for those six and a half hours, we looked up at a sky that drizzled us with mocking rain and then laughed through a thick layer of clouds.

For other reasons than the fact of absolute minimal sunlight, today--and this past week--has been very dark. I grew up in Connecticut, and hearing the news about Sandy Hook rattled me. Like many people, I found myself weeping.

In the flurry of articles that have come out in this past week, none is able to articulate exactly why this kind of tragedy is pepetuating itself over and over again. But one area that continues to go unexamined by most social theorists and also those in the media is the area of gender. Jackson Katz and Byron Hurt are doing their part to discuss why of the 62 mass killings on American soil, 61 of them have been commited by men. Katz powerfully reasons that if the opposite were true, and 61 of the 62 mass killings had been perpetrated by women, all we would hear and read would be about the gendered nature of the crimes.

As a society, the way we socialize men is dangerous and we see this over and over again. The 61 mass murders are the highest form of the tragedy, but every day we see lesser versions--no less horrendous to the victims, however--of gendered violence: we see men killing men in gang warfare; we see men fighting men for pride, revenge, or to prove their masculinity.

In essence, we see men learning repeatedly--from father, from film, from heroes and mentors--that the only way to be a man is to be tough, violent, and aggressive. Men are not revered for their compassion, gentleness, empathy, and their tears.

I think one reason why Harper Lee's Atticus Finch stands so tall after all these years is that Lee artciluated through fiction an idea of what genuine strength in masculinity could look like.

It could look like going against the bullying culture so many men are bred into and indoctrinated towards. It could look like self-reflection rather than blame. It could look like an end to attacks and harassment (whether through words or actions) and a commencement of authentic listening--asking what it's really like to walk in the shoes of other people, whether minorities, females, homosexuals, or transgendered people.

Until we come face to face with a fraction like 61/62, we are going to be missing an underlying cause of the violence we continue to see in every city of every state of our country. Masculinity does not have to be defined by aggression, violence, tough-talk, and lack of empathy.

After the sun had set today, Jennifer and I watched Tyler run back and forth through our kitchen and hallway as we blasted Enya's Winterland CD. He was laughing, running, laughing, running, giggling.

Tyler is four years old.

He is my son.

The question I am faced with as a father, and the question we are all faced with as members of an American society, is this: How we can we teach boys that to grow into men does not mean to lose one's ability to giggle, to weep, to show compassion, empathy, tenderness, and vulnerability?

It is time we make heroes not only of those who hold a gun--whether in films or in real life--but also of those who hold a hand. If we can learn, as men, to move forward hand in hand--vulnerable, honest, authentically strong--rather than as aggressive lone rangers, I think American society will see massive shifts. Our darkest days--no matter when the sun sets--may yet transmogrify into our brightest possibilities.

For other reasons than the fact of absolute minimal sunlight, today--and this past week--has been very dark. I grew up in Connecticut, and hearing the news about Sandy Hook rattled me. Like many people, I found myself weeping.

In the flurry of articles that have come out in this past week, none is able to articulate exactly why this kind of tragedy is pepetuating itself over and over again. But one area that continues to go unexamined by most social theorists and also those in the media is the area of gender. Jackson Katz and Byron Hurt are doing their part to discuss why of the 62 mass killings on American soil, 61 of them have been commited by men. Katz powerfully reasons that if the opposite were true, and 61 of the 62 mass killings had been perpetrated by women, all we would hear and read would be about the gendered nature of the crimes.

As a society, the way we socialize men is dangerous and we see this over and over again. The 61 mass murders are the highest form of the tragedy, but every day we see lesser versions--no less horrendous to the victims, however--of gendered violence: we see men killing men in gang warfare; we see men fighting men for pride, revenge, or to prove their masculinity.

In essence, we see men learning repeatedly--from father, from film, from heroes and mentors--that the only way to be a man is to be tough, violent, and aggressive. Men are not revered for their compassion, gentleness, empathy, and their tears.

I think one reason why Harper Lee's Atticus Finch stands so tall after all these years is that Lee artciluated through fiction an idea of what genuine strength in masculinity could look like.

It could look like going against the bullying culture so many men are bred into and indoctrinated towards. It could look like self-reflection rather than blame. It could look like an end to attacks and harassment (whether through words or actions) and a commencement of authentic listening--asking what it's really like to walk in the shoes of other people, whether minorities, females, homosexuals, or transgendered people.

Until we come face to face with a fraction like 61/62, we are going to be missing an underlying cause of the violence we continue to see in every city of every state of our country. Masculinity does not have to be defined by aggression, violence, tough-talk, and lack of empathy.

After the sun had set today, Jennifer and I watched Tyler run back and forth through our kitchen and hallway as we blasted Enya's Winterland CD. He was laughing, running, laughing, running, giggling.

Tyler is four years old.

He is my son.

The question I am faced with as a father, and the question we are all faced with as members of an American society, is this: How we can we teach boys that to grow into men does not mean to lose one's ability to giggle, to weep, to show compassion, empathy, tenderness, and vulnerability?

It is time we make heroes not only of those who hold a gun--whether in films or in real life--but also of those who hold a hand. If we can learn, as men, to move forward hand in hand--vulnerable, honest, authentically strong--rather than as aggressive lone rangers, I think American society will see massive shifts. Our darkest days--no matter when the sun sets--may yet transmogrify into our brightest possibilities.

Wednesday, December 12, 2012

What it Comes Down To

I've just gotten off the phone with Dr. Noam Chomsky. For an upcoming book on education tentatively entitled IMAGINE: Visions of What School Might Be, I had the chance to interview Dr. Chomsky, and it was a powerful experience--made even more powerful by the fact that I was calling on a tiny little Magic Jack device that helped me place the call from York, England to Cambridge, Massachusetts and only once during the 25-minutes did the device go haywire and almost hang the call up. Crisis averted, and our discussion was inspiring.

After recently finishing Diane Ravitch's utterly compelling and deeply important book, The Death and Life of the Great American School System, I have become more and more excited about the revival of the American Public School system.

Sure, it looks bleak right now, with market-based principles and privatization rampantly encroaching on a basic human right of children. Billions have been spent pressuring teachers to narrow their curriculum so that high-stakes testing becomes the sole focus on schools. What is lost is love of learning, authentic growth, development as citizens, the values of compassion, and the ethic of collaboration.

And yet, we're still standing as a crossroads. Even with the heavy financing of powerful foundations to pressure both the federal government and state governments to work towards competition and market-based principals in schools, somehow, the public school system remains undaunted. Even with vociferous attacks on teachers and teacher unions--media and Hollywood providing the microphones--the public schools system holds as its steadfast mission to reach and teach all children: not just those who can provide better test scores. But the children in special ed programs, the English Language Learners, those with severe behavorial issues--all children.

As a young high school student, I remember watching Morgan Freeman in the film Lean on Me. Originally, I was riveted by Freeman's portrayal of real-life principal Joe Clark. After all, he was tough. He did the dirty work of getting rid of all the "bad" kids. Gathered them on stage and kicked them out so that he could inspire, motivate, and teach the kids who really wanted to learn.

Right on! And, obviously, the media loved the figure of Joe Clark enough to make a movie about him.

These many years later, however, I see the film in a new light. For the first time, I am asking, What happened to all those 'bad' kids? Where did they go? If they were kicked out of public school, then what?

And when I think of similar get-tough figures from our current era--like Michelle Rhee and Joel Klein--an interesting trend asserts itself. We glorify those leaders who talk tough and place blame. Whether it's the bad kids in Joe Clark's Eastside High or the underperforming teachers in Michelle Rhee's District of Columbia, we find outlets to praise those who talk tough and point fingers.

And yet: a stubbornly troubling fact asserts itself. If we blame the bad kids and get rid of them, and if we blame the bad teachers and get rid of them--but the system still doesn't improve, what are we left with?

We find ourselves, then, where we should be beginning anyway: by examining the system itself. How can we truly expect public schools to thrive when funding is based on unequal measures--so that students in poor areas consistently receive vastly lower funding and vastly larger class sizes than students in affluent areas? (This was documented in great detail by Jonathan Kozol in his heartbreaking book Savage Inequalities two decades ago. The book was promptly praised by the press, then promptly ignored by policy-makers and today, that system of unequal funding is largely unchanged.)

How can we truly expect public schools to thrive when teachers are being pressured constantly to raise test scores, thereby spending vast amounts of class time teaching students test-taking skills that will become wholly meaningless skills after they leave high school. Where in the workforce or larger world community do people ask us to take multiple choice tests to prove our worth, abilities, or work ethic? Nowhere. We reveal and demonstrate these qualities via our social interactions, experiences, collaborations, and projects.

How can we truly expect public schools to thrive when we underfund them, overload teachers, pressure leaders to get test results, do nothing to change the status quo of the plight of those in poverty, and then hand 30 students to a teacher and say, get results?

Instead of brow-beating and pointing fingers, this is a time to support students and teachers alike: smaller class sizes for all teachers, increased autonomy and ability to be creative and interactive in classrooms, instead of narrowing the curriculum to focus on standardized test-scores, open it up to possibilities for authentic learning motivated intrinsically. Create ways to help those students with behavioral issues to change and learn new skills rather than kicking them out to the streets. Welcome all students--not just those privatization would encourage us to welcome because they represent possible rises in test scores.

Tonight, one of the things that most moved me about what Dr. Chomsky shared was his response to a question about switching the current trend in education, and some of his answer is a fitting way to close:

The public school system is based on the idea that we do care about other people. That’s what it comes down to. Charter schools undermine the public schools, and the other problem is that schools are very much underfunded, and if you want to destroy a system, underfund it and then people will say we’ve got to privatize it. As an example, when Margaret Thatcher wanted to destroy the public transportation system in Britain, she underfunded it, then she privatized it. That’s what is happening with the schools now.

After recently finishing Diane Ravitch's utterly compelling and deeply important book, The Death and Life of the Great American School System, I have become more and more excited about the revival of the American Public School system.

Sure, it looks bleak right now, with market-based principles and privatization rampantly encroaching on a basic human right of children. Billions have been spent pressuring teachers to narrow their curriculum so that high-stakes testing becomes the sole focus on schools. What is lost is love of learning, authentic growth, development as citizens, the values of compassion, and the ethic of collaboration.

And yet, we're still standing as a crossroads. Even with the heavy financing of powerful foundations to pressure both the federal government and state governments to work towards competition and market-based principals in schools, somehow, the public school system remains undaunted. Even with vociferous attacks on teachers and teacher unions--media and Hollywood providing the microphones--the public schools system holds as its steadfast mission to reach and teach all children: not just those who can provide better test scores. But the children in special ed programs, the English Language Learners, those with severe behavorial issues--all children.

As a young high school student, I remember watching Morgan Freeman in the film Lean on Me. Originally, I was riveted by Freeman's portrayal of real-life principal Joe Clark. After all, he was tough. He did the dirty work of getting rid of all the "bad" kids. Gathered them on stage and kicked them out so that he could inspire, motivate, and teach the kids who really wanted to learn.

Right on! And, obviously, the media loved the figure of Joe Clark enough to make a movie about him.

These many years later, however, I see the film in a new light. For the first time, I am asking, What happened to all those 'bad' kids? Where did they go? If they were kicked out of public school, then what?

And when I think of similar get-tough figures from our current era--like Michelle Rhee and Joel Klein--an interesting trend asserts itself. We glorify those leaders who talk tough and place blame. Whether it's the bad kids in Joe Clark's Eastside High or the underperforming teachers in Michelle Rhee's District of Columbia, we find outlets to praise those who talk tough and point fingers.

And yet: a stubbornly troubling fact asserts itself. If we blame the bad kids and get rid of them, and if we blame the bad teachers and get rid of them--but the system still doesn't improve, what are we left with?

We find ourselves, then, where we should be beginning anyway: by examining the system itself. How can we truly expect public schools to thrive when funding is based on unequal measures--so that students in poor areas consistently receive vastly lower funding and vastly larger class sizes than students in affluent areas? (This was documented in great detail by Jonathan Kozol in his heartbreaking book Savage Inequalities two decades ago. The book was promptly praised by the press, then promptly ignored by policy-makers and today, that system of unequal funding is largely unchanged.)

How can we truly expect public schools to thrive when teachers are being pressured constantly to raise test scores, thereby spending vast amounts of class time teaching students test-taking skills that will become wholly meaningless skills after they leave high school. Where in the workforce or larger world community do people ask us to take multiple choice tests to prove our worth, abilities, or work ethic? Nowhere. We reveal and demonstrate these qualities via our social interactions, experiences, collaborations, and projects.

How can we truly expect public schools to thrive when we underfund them, overload teachers, pressure leaders to get test results, do nothing to change the status quo of the plight of those in poverty, and then hand 30 students to a teacher and say, get results?

Instead of brow-beating and pointing fingers, this is a time to support students and teachers alike: smaller class sizes for all teachers, increased autonomy and ability to be creative and interactive in classrooms, instead of narrowing the curriculum to focus on standardized test-scores, open it up to possibilities for authentic learning motivated intrinsically. Create ways to help those students with behavioral issues to change and learn new skills rather than kicking them out to the streets. Welcome all students--not just those privatization would encourage us to welcome because they represent possible rises in test scores.

Tonight, one of the things that most moved me about what Dr. Chomsky shared was his response to a question about switching the current trend in education, and some of his answer is a fitting way to close:

The public school system is based on the idea that we do care about other people. That’s what it comes down to. Charter schools undermine the public schools, and the other problem is that schools are very much underfunded, and if you want to destroy a system, underfund it and then people will say we’ve got to privatize it. As an example, when Margaret Thatcher wanted to destroy the public transportation system in Britain, she underfunded it, then she privatized it. That’s what is happening with the schools now.

Tuesday, December 11, 2012

One True Thing from Angela Ackerman: Kindness is Contagious

Kindness is Contagious

By Angela Ackerman

I really only have one moral belief that I

follow in life: if you can help, do.

This mantra guides me as I interact with people, make decisions, and plan my

future. I like to be there for others, and contribute to their happiness and

success if I can.

It doesn't always work out of course. Like

the time a crazy hell cat ran into a neighbor’s house because I had called on

her to inquire if a lost cat I’d found was hers (It wasn't But to be fair,

they looked almost identical). And then there was the time my other security

conscious neighbor drove off, leaving her garage door wide open, so I closed it

for her. (And then subsequently had to help her break into her own house when

she returned because her garage door had malfunction and wouldn't open.) Hmm. I

see a pattern here: Me. Neighbors.

Kindness backfiring. Perhaps I

should think twice about anything involving neighbors?

But back to the meat and potatoes. Why do

people proactively do things for others? The small things. Simple gestures. Bits

of kindness that aren’t necessary, but people do anyway.

I think it’s because deep down we hope that

kindness will inspire kindness.

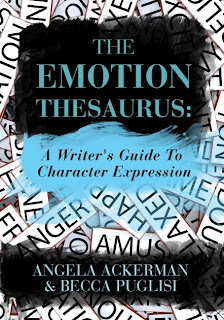

When it came time for our Emotion Thesaurus

book launch, Becca and I knew one thing: we were not comfortable waving our book

and asking people to buy it. That’s just wasn't us. So we decided to do

something we could get very excited about, something we believed in: proving

that kindness will pay forward.

Our launch initiative involved convincing one

hundred writer/bloggers, in secret, to do a Random Act Of Kindness for another

writer and post about it on their blog on the same day (our release date). We

created a week-long event for this, with prizes each day that people could try

to win, prizes donated by industry professionals like Scrivener and Writer’s

Digest who believed in what we were trying to do.

The first day was amazing. One hundred Acts

of Kindness hit the WWW, things that included small gifts, shout outs, offers

to read work and more. The people who were on the receiving end were blown away

that someone they knew in the writing community would single them out so

thoughtfully. Words of gratitude swam across the internet. It was great!

When day two came along, Becca and I held

our breath. Would the kindness roll forward

as we believed? Would people be inspired by our Kindness Blitz?

And you know what? By the end of the week,

we estimate that over 200 bloggers joined Random Acts of Kindness for Writers.

So my one true thing is simply this: Kindness not only brings about amazing

things...it is also contagious!

Angela Ackerman is one half of The Bookshelf Muse blogging duo, and co-author of The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression. Listing the body language, visceral reactions and thoughts associated with seventy-five different emotions, this brainstorming guide is a valuable tool for showing, not telling, emotion.

Angela Ackerman is one half of The Bookshelf Muse blogging duo, and co-author of The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer’s Guide to Character Expression. Listing the body language, visceral reactions and thoughts associated with seventy-five different emotions, this brainstorming guide is a valuable tool for showing, not telling, emotion.

Wednesday, December 5, 2012

One True Thing from Matthew Reynolds: Proving and Disproving

When I think of my brother Matthew, it's sometimes hard not to think of him as a two-year old boy, laying in his bed while my teenage self told stories to him and my other younger brother, Bryan. Laying in their beds, they'd go along with any crazy, silly, ridiculous stuff I shared, and each night as they drifted to sleep, I watched them wondering what kind of people they'd grow up to be.

So it's still a little difficult to think of Matthew as a young man earning a doctorate in physical therapy from Quinnipiac University. However, everytime I see him and realize that his pecs and biceps are about four times the size of mine, I realize that he has, indeed, grown up. Matthew has a deeply inspiring sense of humor, and he makes all those around him feel at home both with themselves and with him. He embodies that beautiful golden rule and treats other people with the kind of dignity, respect, and compassion with which he wants to be treated. Matthew works with passion and commitment and is a firm believer in the power of getting up again, and again, and again.

And he still likes silly stories.

Here is Matthew Harry Wilson Reynolds the Fourth, sharing his One True Thing.

Proving and Disproving

By Matthew Reynolds

So it's still a little difficult to think of Matthew as a young man earning a doctorate in physical therapy from Quinnipiac University. However, everytime I see him and realize that his pecs and biceps are about four times the size of mine, I realize that he has, indeed, grown up. Matthew has a deeply inspiring sense of humor, and he makes all those around him feel at home both with themselves and with him. He embodies that beautiful golden rule and treats other people with the kind of dignity, respect, and compassion with which he wants to be treated. Matthew works with passion and commitment and is a firm believer in the power of getting up again, and again, and again.

And he still likes silly stories.

Here is Matthew Harry Wilson Reynolds the Fourth, sharing his One True Thing.

Proving and Disproving

By Matthew Reynolds

|

| Matt at the end of No-Shave-November |

For me, it’s difficult to believe in one

true thing. When my brother Luke asked me to write a brief synopsis of my

opinion, I thought more about the simple question. The simple question turned

into many more questions, which turned into more questions, and on and on.

What’s my point you ask? Let’s take a look at some true things. The world used

to be flat hundreds of years ago. The earth was also the center

of the universe and everything revolved around this magnificent planet.

Truths

are replaced by disproven theories.

It is true, although, that old truths are

replaced by new truths. That, my friend, is the beauty of learning. The only truth

is that we will disprove, discover, and learn new truths. That is the only real truth in life.

From the second we are born, our

brains are taking the huge needle of life and injecting knowledge, ideas,

passions, loves, despairs, lies, and truths. Throughout life, we are constantly

changing. We are proving and disproving our own beliefs. Therefore, a truth is

no more than what we believe. That is the BEAUTY of it.

Ayn Rand once said,

“Every man is free to rise as far as he is able or willing, but it is only the

degree to which he thinks that determines the degree to which he’ll rise.” This

quote speaks truths to my ears. The reason we can thrive, prosper, and grow is

because each person has their One True Thing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)